|

Dale Stastny, the Executive Vice President

and Chief Operating Officer said in a November

interview, "I do see a correlation between whatís happening now and

what happened in 1975. The neighbors and other people fought the

zoo for five years, and they lost. It got built and you would probably

be hard pressed to find more than one or two people who would admit that

they didnít want the zoo."

Dale Stastny is an employee of the Audubon

Institute, which is oftentimes confused with the Audubon Commission.

The members of the Commission are Mayor-appointed for four years.

They are the public body charged with the upkeep of Audubon Park and they

are not paid. In order to run the park efficiently, they hired the

Audubon Institute to take over the day-to-day maintenance. The Institute

is given no public operational money, but they are given capital money

to use in projects. These projects in turn generate operational money.

A contract was approved on October 24, 2001

that stated that the Commission will accept, for a duration of 10 years,

the CEO of the Institute. [Editor's note, this agreement was subsequently changed to

allow the CEO of the Institute to execute documents on behalf of the Commission without

actually becoming the CEO of the Commission]

The newly renovated golf course is to serve

as a money making project, with the new green fees approximately triple

of what they were. It will now cost $18 on weekdays and $25 on weekends

to play the course. There will also be a revenue-generating pro shop,

cart rental, and restaurant in the new Clubhouse.

One lesson that we learned with our research

was that non-profit in no way equals poor. To see an example of this,

look at our worksheet on the salary of Mr. L. Ron Forman, CEO of the Institute [not available to s.a.p

but his salary for his work with Audubon is around $360,000 per year]

The new golf course will still have 18 holes,

but it will be par 62 (a normal golf course is par 72). Two kinds

of Bermuda grass will be used for landscaping and four new lagoons will

be dug. The Meditation Walk will be moved about 20 feet and re-landscaped.

The Hurst bridge and the Hurst walk are still in question. The Institute

has not decided what the policy will be for access to these two areas.

There are safety and liability issues about allowing non-golfers to walk

on the golf course. Stastny suggested that there might be a

system where access would be allowed during certain hours with certain

sign-in [signage?] rules.

Also, a new clubhouse is to be built. On

the Audubon Instituteís website,

the purpose of the clubhouse is listed:

"The primary purpose of the

clubhouse is to provide for the administration of the golf course (pro-shop,

green fee purchases, cart rentals, golf pro administrative and storage

space and location for managing the day time activities on the course).

It also must provide for the physical comfort and needs of the individuals

using the golf course (restrooms, food service, changing room and a place

to wait or relax before or after golf)."

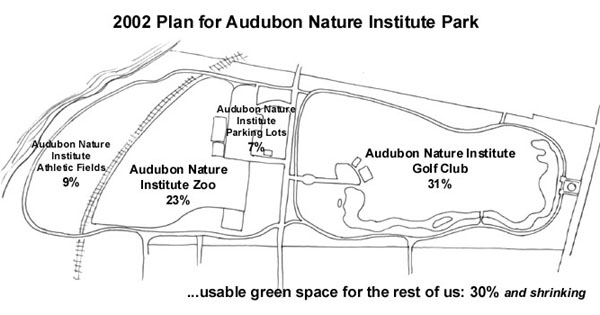

This brings us to the arguments of grass roots

organizations who are opposed to action of the Audubon Institute.

The Audubon Institute stands firm in its claim that the golf course is

not expanding. Its opponents recognize that no new space in the park

has been dedicated as green space. However, more parking spaces are

being paved and the clubhouse and equipment storage are taking up space

in an oak grove that stretches from Magazine to the golf course.

The opponents are argue that the public is still losing green space in

what is, after all, a public park. The following cartoon was taken

from the Save Audubon Park website

Many also dread the environmental impact that

the course will have. It happens that the fine, short, and delicate

Bermuda grasses that the Institute chose are not well-suited for Louisiana

life. They are highly susceptible to Dollar Spot Fungus in warm and humid weather.

This kind of fungus requires three different kinds of fungicides used in

rotation plus extra fertilizer. This treatment normally leads to

the weakening of the natural defenses of the grass, and infestation of

other pests, fungi, or bacteria is likely.

I questioned Dale Stastny as to whether anything

had been done to make the course ecologically friendly. He told me,

"We are an environmental organization. Itís not like this is an

area in which we are uncaring or ignorant. The specifics of this,

with the golf course, we are not very knowledgeable right now, but we will

be. It will be consistent with all of our past actions."

And to that statement, the opponents say, "Thatís

what weíre afraid of." The Audubon Institute has a long history of

mutual back-scratching with oil and land development companies and a track

record that is sometimes not so becoming to an "environmentalist, conservationist"

organization. The Audubon Institute has long been a member of the

National Wetlands Coalition, whose name sounds benign and rather like a

conservation organization. This is the organization of mostly oil

companies and land-developers (with the sole exception of the Audubon Institute)

that is dedicated to the rolling back of wetlands protection policies in

favor of wetlands exploration. They drafted and sponsored the Shuster

Bill, nicknamed the Dirty Water Bill, in 1995. This bill aimed to

take away the oversight of the EPA awarded in the Clean Water Act.

Leighton Steward, CEO of Louisiana Land & Exploration Company, is a

founding member of this group. It is the statesí largest landowner

with nearly 1,000 square miles of coastal Louisiana in its name and environmental

regulations imposed by the federal government cause financial loss to the

corporation. This is group is in favor of reducing the Clean Water

Act and the federal protection of endangered species.

The Audubon Institute often lists their membership

to the National Wetlands Coalition as just another great thing that they

do for the environment on its long lists of memberships. But why

would the Audubon Institute join a group like this? There have been

public accusations since 1995 that Ron Forman is simply "singing for his

supper." Perhaps it was best stated by the Times-Picayune writer

Steward Yerton, who said in his 1995 article, "Force of Nature":

"A tour of the Audubon facilities is like a stroll on the mining and oil

and gas exploration hall of fame."[Emphasis added].

Members of Save Audubon Park point out that the

Ron Forman and his Institute are merely in the business of animal entertainment

and they would like to see their business grow.

Audrey Evans, community outreach coordinator for

the Tulane Environmental Law Clinic, told the Times-Picayune in the above

article, "Itís disturbing that the public could be so confused. The

public should be informed that a group they are supporting through zoo

memberships is also on record consistently continuing to associate with

forces who are actively working to destroy the wetlands."

Also quoted in the article is Elizabeth Raisbeck

of the National

Audubon Society in Washington, D.C: "You will not find any bona fide environmental groups on the membership

list."

[

This review of the Audubon Park controversy was prepared in support of a paper on the subject of the

Four-Quadrant theory for a "Full-Spectrum" approach to problem solving. For more on this theory and how it relates

to Audubon Park click here.]

|